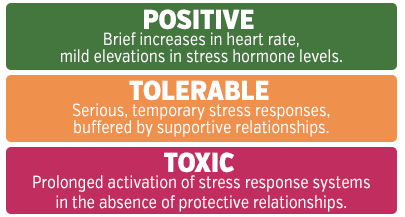

Stress is the body’s physiological and cognitive response to situations/events we perceive as threats or challenges. It is a normal and natural response. The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child proposed three distinct forms of stress responses in young children: Positive, tolerable, and toxic.1, 2

Let’s start with the latter because it is considered as the most dangerous or harmful type of stress response. Exposure to stressful and adverse experiences over a long period of time can become toxic. This repeated exposure to stress without the benefit of buffering protection of a supportive, adult relationship has been termed toxic stress.1, 2

Several adverse life events may contribute to toxic stress response include neglect and abuse, divorce/separation, death of a loved one, exposure to domestic violence, incarceration of a parent or a family member, neighborhood violence, extreme poverty, parent or family member abusing drugs/alcohol, parent or caregiver having a mental illness, neglect. Exposure to toxic stress can have detrimental short and long-term physical and mental health consequences on both children and adults.

Research has shown when an individual appraises a situation as being stressful, the adrenal medulla releases the hormone adrenaline, which prepares the body for a fight or flight response.3 This increases heart, sweating, blood pressure, and breathing rates. The hypothalamus, which is a brain structure associated with emotional reactions, such as fear responds to stress by activating the pituitary gland, which in turn secretes adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that activates the adrenal glands to release the hormone corticosteroid. Cortisol helps the body to maintain steady supplies of blood sugar.

When the stress response (flight/fight response) is activated. It is important to get it back to its baseline. Learning to relax can play a tremendous difference in alleviating stress. This can be achieved by activating the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) to elicit what Dr. Benson termed the relaxation response, which is a “physical state of deep rest that changes the physical and emotional responses to stress.”4 The relaxation response works in the opposite way of the fight-or-flight response. It lowers the stress hormone levels and lowers blood pressure.

A positive stress response refers to a physiologic state that is brief and mild to moderate in magnitude.”1 This type of stress response can be alleviated with the assistance of a caring and responsive adult who help the child cope with the stressor. In this context, the presence of a caring and responsive adult plays the role of a protective factor because it allows the child’s stress response to return to the original state or baseline. Examples of stressors that trigger positive response in children include dealing with frustration, anxiety associated with being in novel situations or environments, getting immunization.

A tolerable stress response is associated with exposure to non-normative experiences that present a greater magnitude of adversity or threat.”1 Examples of this type of stress response include experiencing the death a family member, a serious illness or injury, natural disaster, an act of terrorism. What makes this types of stress response tolerable is having the protection provided supportive adult relationships that enhances the child’s ability to cope and gain a of sense control. This helps to “reduce the physiologic stress response and promote a return to baseline status.

In order to reduce the effects of toxic stress on children’s health, it is important to not only to identify its risk and protective factors, but also empower families by helping them to develop and bolster protective factors, such as resilience. The National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2009) define protective factors as “a characteristic at the biological, psychological, family, or community level that is associated with lower likelihood of problem outcomes or that reduces the negative impact of a risk factor on problem outcomes” (p. xxvii). Risk factors refer to as “a characteristic at the biological, psychological, family or cultural level that precedes and is associated with a higher likelihood of problem outcomes” 5 (p. xxvii).

In children, risk factors for toxic stress include neglect and abuse, family violence, extreme poverty, substance abuse, and parental mental health problems.6,7 However, it should be noted that not every child who was exposed to adversity, or toxic stress develops health problems.

Research has shown that protective factors, such as resiliency, and strong social and emotional support buffer the effects of toxic stress. Some children are resilient. Resilience is the “ability to adapt well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress.” It is the ability to bounce back from difficult experiences. Several factors play a role in resilience including personality, biology, high IQ, empathy, social problem-solving.8